Welcome back to the Short Fiction Spotlight, a weekly column co-curated by myself and the inestimable Lee Mandelo, and dedicated to doing exactly what it says in the header: shining a light on the some of the best and most relevant fiction of the aforementioned form.

Last time I directed the Short Fiction Spotlight, we discussed two terrific novelettes in which image was everything. Both were nominated for a Nebula. By now, the winners of that award—and all the others on the roster, obviously—will have been announced, and much as I might have liked to look at those this week, these columns aren’t researched, written, submitted, formatted and edited all on the morning of.

So what I thought I’d do, in the spirit of keeping the Nebula news alive a little longer, was turn to a pair of tales whose authors were honoured in 2012 instead. To wit, we’ll touch on “What We Found” by Geoff Ryman in short order, but let’s begin this edition of the Short Fiction Spotlight with a review of “The Paper Menagerie” by Ken Liu.

I probably need not note that the Nebula for Best Short Story wasn’t the only prize “The Paper Menagerie” picked up, but in the unlikely event you weren’t aware, Liu’s quietly fantastical contemplation of love and loss swept all the major genre awards last year. Which is to say it was awarded a Hugo and a World Fantasy Award as well, becoming the first work of fiction to take all three of these coveted trophies home.

I remember idly wondering why that was when I read “The Paper Menagerie” for the first time sometime last summer. I don’t mean to appear contrary here: Liu’s was certainly a touching tale, and perfectly well put to boot, but the fact that the community was practically unanimous in its veneration of this short story seemed—at least to me—symptomatic of a relatively meagre year for the form.

Reading it again now—which you too can do, via io9 or perhaps in the pages of the new Nebula Awards Showcase collection, edited this annum by Catherine Asaro—“The Paper Menagerie” moved me in a way it couldn’t quite at the time.

It’s about a boy, born in the Year of the Tiger, who becomes a man before the story’s over, and reflects, from that perspective, on how sorry a thing it is that his mother died before he got to know her as a person as opposed to a parent:

For years she had refused to go to the doctor for the pain inside her that she said was no big deal. By the time an ambulance finally carried her in, the cancer had spread far beyond the limits of surgery.

My mind was not in the room. It was the middle of the on-campus recruiting season, and I was focused on resumes, transcripts, and strategically constructed interview schedules. I schemed about how to lie to the corporate recruiters most effectively so that they’ll offer to buy me. I understood intellectually that it was terrible to think about this while your mother lay dying. But that understanding didn’t mean I could change how I felt.

She was conscious. Dad held her left hand with both of his own. He leaned down to kiss her forehead. He seemed weak and old in a way that startled me. I realized that I knew almost as little about Dad as I did about Mom.

“The Paper Menagerie” takes in scenes spread across many years of our narrator’s life, from both before and after his mother’s passing. He remembers the happy days, when she would fold enchanted origami animals that lived just for him, and the sad. He recalls the loss of Laohu, the paper tiger she fashioned out of offcuts one Christmas, and how his desire to fit in with his friends led him to fall out with his family.

To be sure, these sequences have the ring of the real about them—up to and including those involving Laohu and the like, for though the titular menagerie is animated by magic, we have all in our lives treasured inexplicable objects and ideas; childish things I dare say we have had to put away, later, as our protagonist feels he must at a point.

“The Paper Menagerie” is a lump in your throat sort of short from early on, but what broke my heart whilst revisiting it was the way in which the son rediscovers his mother. There’s such beauty to the thing—the silly, innocent, magnificent thing—that finally brings the whole story and the arc of our regret-ridden central character into focus… such simple beauty, yet such startling truth, too.

I can tell you exactly why “The Paper Menagerie” affected me more this time than it did the last: it’s a very personal story, about an unimaginably intimate subject, and beforehand, Liu’s central character simply didn’t speak to me. Today, things are different.

I count myself lucky, looking back; as much as I feel a fool for missing what made this poignant portrait resonate with so many, I’d give almost anything to have that lack back. Ignorance is indeed bliss.

But moving on—because we must, mustn’t we?—“The Paper Menagerie” uses the fantastic to depict a dysfunctional family with such depth and tenderness that I no longer question whether it merited the many accolades it was awarded. Speculative elements also figure into Geoff Ryman’s “What We Found,” which is another narrative about family, similar but different from the first tale we discussed today, and a winner in its own right—of the 2012 Nebula Award for Best Novelette, and somewhat less significantly, my admiration… if not my wholehearted adoration.

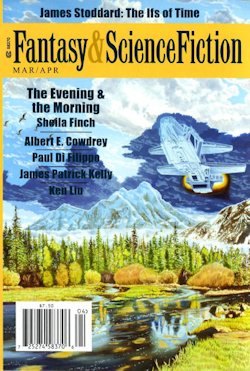

First published in The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction, “What We Found” tells the story of a noted Nigerian researcher who, on the morning of his marriage, harkens back to his beginnings, wondering how he became the man he has become, and what wisdom he has, or has not, to pass on. Intermittently, Patrick—or Terhemba, to use the Tiv name his elder brother wields like a weapon—relates his childhood experiences to certain experiments he has conducted in the years since:

People think Makurdi is a backwater, but now we have all you need for a civilized life. Beautiful banks with security doors, retina ID and air conditioning; new roads, solar panels on all the streetlights, and our phones are stuffed full of e-books. On one of the river islands they built the new hospital; and my university has a medical school, all pink and state-funded with laboratories that are as good as most. Good enough for controlled experiments with mice.

My research assistant Jide is Yoruba and his people believe that the grandson first born after his grandfather’s death will continue that man’s life. Jide says that we have found how that is true. This is a problem for Christian Nigerians, for it means that evil continues.

What we have found in mice is this. If you deprive a mouse of a mother’s love, if you make him stressed through infancy, his brain becomes methylated. The high levels of methyl deactivate a gene that produces a neurotropin important for memory and emotional balance in both mice and humans. Schizophrenics have abnormally low levels of it.

These passages—wherein Ryman questions the consequences of genetic inheritance, among other such subjects—these passages showcase the most intellectually absorbing moments of the story, but emotionally, “What We Found” is all about a boy. Or rather, a boy and his father, a boy and his mother, and, at the very heart of this narrative, a boy and his brother.

They appear a perfectly functional family at first, but as their circumstances change—as they shift from riches to rags as opposed to the typical trajectory—the unit unravels entirely. Patrick’s father has always been a little different from other dads, but when he loses his job, his strange behaviour takes a turn for the worse, meanwhile Mamamimi seems to disappear.

In the midst of these bleak upheavals, Patrick and Raphael find respite in the company of one another, delighting in the bond that forms between brothers. Alas, other ties bind the boys; ties analogous to the studies of schizophrenia in methylated mice an elder Patrick instigates.

If the truth be told, “What We Found” isn’t a story you should read for the science fiction, or even the fictional science. There’s so very little of either thing about it… but what there is integrates elegantly with the more mundane part of the narrative. Each academic interlude informs the next arrangement of everyday recollections in a way which both shapes and distorts our expectations.

I do think Ryman could have struck a better balance between these otherwise isolated points in Patrick’s life. As it stands, “What We Found” feels overlong, the basis for a truly superb short story instead of a reasonably impressive novelette. Readers will realise what the author is driving at a while before the wheels start to turn, and though “What We Found” has thrust enough—just—to carry it through this dreary period, its narrative is not substantial enough to support such ample characters.

So “What We Found” doesn’t ultimately pack the same punch as “The Paper Menagerie,” but both stories take advantage of the fantastic and the mark it makes on the mundane to illuminate fascinating aspects of family. I can only hope the winners of this year’s assorted Nebula Awards posit an argument half as captivating.

Niall Alexander is an erstwhile English teacher who reads and writes about all things weird and wonderful for The Speculative Scotsman, Strange Horizons, and Tor.com, where he contributes a weekly column concerned with news and new releases in the UK called the British Genre Fiction Focus, and co-curates the Short Fiction Spotlight. On rare occasion he’s been seen to tweet, twoo.